Before the NASA PR rep annihilates me with a strongly worded email, this is a non-NASA affiliated post representing my own personal insight based on already publicly available data. So don’t come after me, please! I’m following the rules!

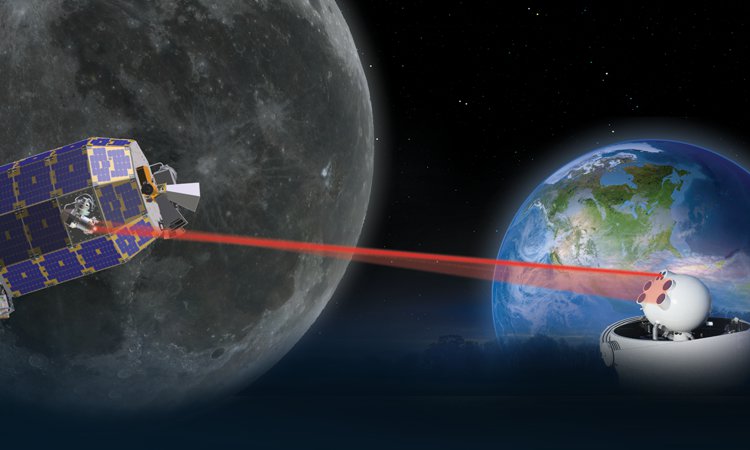

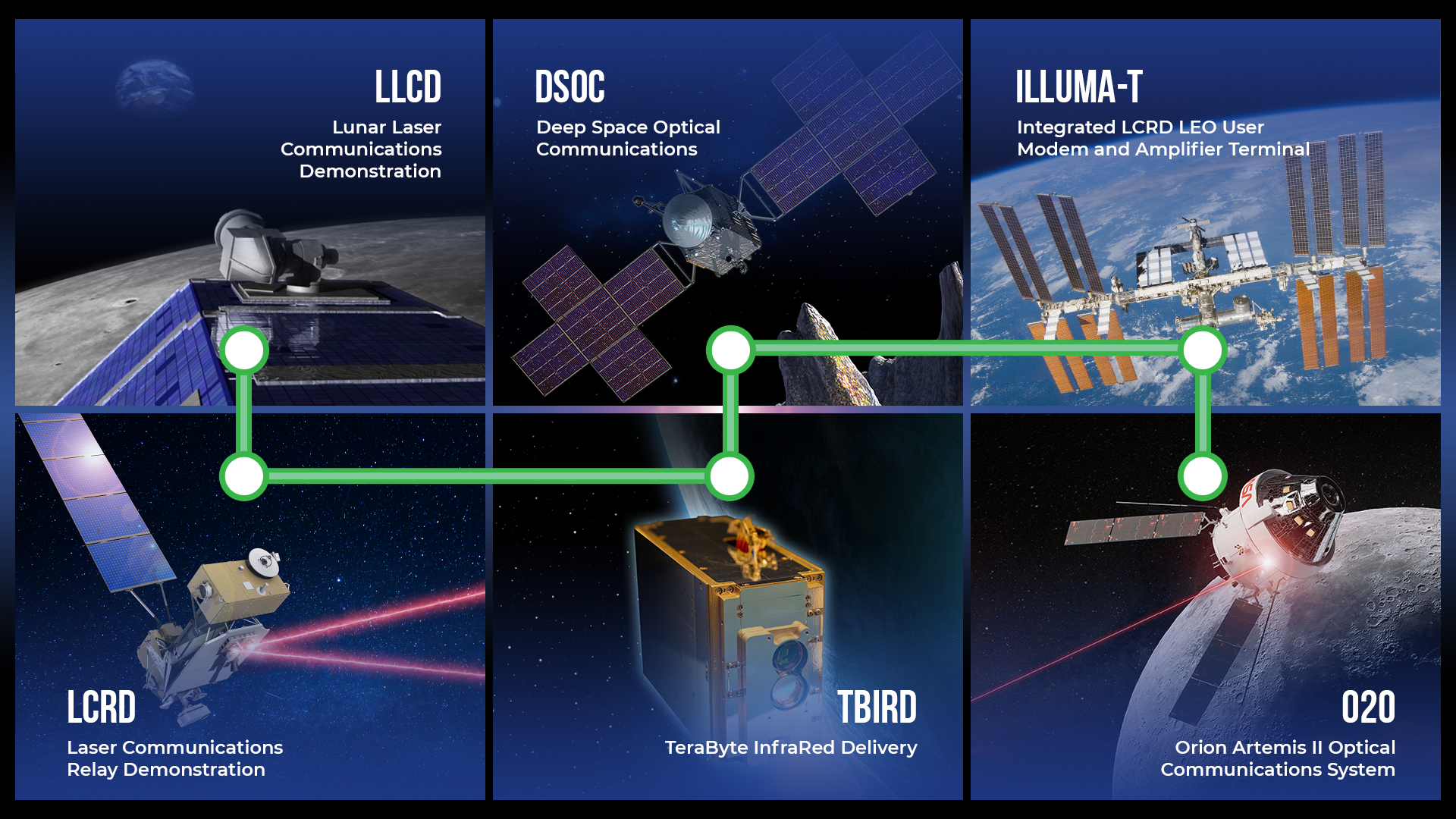

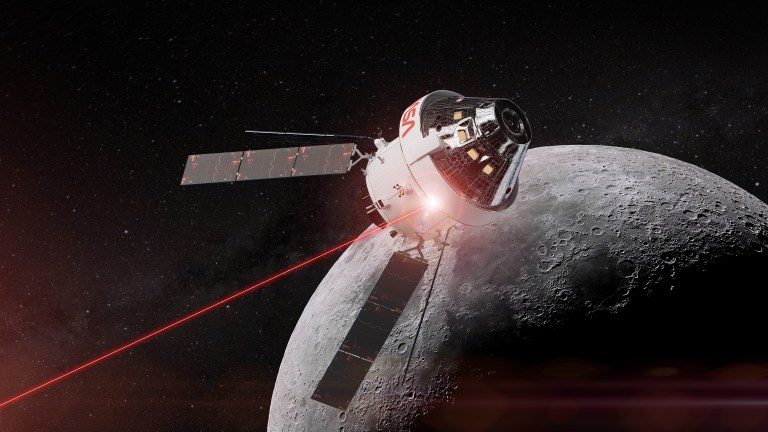

Hey all my adoring fans. I said I would be proactive about making posts on this website, but to everyone’s surprise I haven’t written anything in three months. In my defense, the government reopened and I spent a month in Australia working on an optical ground station at the Australian National University (ANU) to prepare for a deep space lunar communications test from the Orion spacecraft during the Artemis-II mission, currently targeting a launch no earlier than early 2026. As I write this, NASA’s space launch system with the Orion spacecraft has just completed its initial rollout from the vehicle assembly building to the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center, and we eagerly await the wet dress rehearsal. In lieu of this exciting occasion, I thought what better way to reactivate my blog than to talk a bit about deep space optical communication and its involvement in NASA’s Artemis program.

“Laser pointer nerd” I hear you call me, but let me give you some history first before you judge. Optical communication has been around for millennia, dating back to the smoke signals of ancient China around 900 B.C. The Chinese would light fires and use materials like stinky wolf poop to change the properties of smoke to indicate news of invasions along the wall. 750 years later, ancient Greece developed a more sophisticated optical comm technique by encoding messages with paired torches to generate different letters of the alphabet.

Thanks to these trailblazers and 2,750 years of technological advancement, my parents tell the neighbors I shoot lasers from space and my friends’ eyes glaze over while I emotionally unravel about the intricacies of pulse-position demodulation. I promise, I won’t get that detailed. I’m writing this for my parents to send to their friends so they don’t have to feel awkward asking me what I do again (even though I don’t mind).

To my parents and friends, I am an advanced smoke signal engineer and a laser pointer nerd I guess.

Modern deep space optical comm rely on the unimpeded propagation of light in the near-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum to carry information. To put that in more complicated English, optical comm uses light with wavelengths closer to what we can see with our eyes like smoke signals, whereas traditional radio communication (like what your phone might use) uses radio waves. Both use photons to carry information, but visible and infrared light have more energy per photon than radio waves.

So how is optical treated differently than radio and why do we want to use it? Well, most optical communications work is done using light waves and implements many of the same transmitter and receiver ideologies as radio comm. Optical transmission benefits from higher bandwidth (more data per second), are not as congested as radio frequency bands (think two radio stations sharing the same tuning), and are harder to intercept due to the confines of a beam of light. The downside is you need line of sight, but space is called “space” for a reason as there aren’t many obstacles. SpaceX’s StarLink satellite constellation uses optical comm for tens to hundreds of Gbps links between satellites, which benefit immensely from their relatively unobstructed orbits.

That sort of optical comm is ideal for transmitters and receivers in close proximity, but the further you move away from the transmitter and the more stuff you put in between the transmitter and receiver, like clouds and an atmosphere, the harder it is to gather enough light for an optical link. But come on! We want high bandwidth data from deep space missions direct to Earth, too! Think about 4k live streams from multiple cameras from the Moon or Mars in real time alongside instrument telemetry with higher sample rates leading to leaps in scientific progress. In this data driven world, the demand for more data from probes and manned missions beyond Earth is outpacing the capabilities of traditional radio comm, so if you ask me optical comm is a no-brainer. With an increased interest in exploration of deep space along with the budding commercial interest of the lunar surface, optical comm allows for fast data transfers to and from Earth. What then makes deep space comm special, and how do we do it?

Deep space is deep, spacious, and presents a whole new set of challenges. If any of you remember some rudimentary physics, there’s a principle called the inverse square law where light spreads out the further you are from the source. If you aimed a laser pointer at the moon (safely, not in active airspace! Please, FAA, it’s just an example!), you wouldn’t make out any sort of dot on the surface. The light would be too spread out by the time it reaches the Moon. So how do we get any decent laser back to Earth from the Moon in this regime with enough energy that we can actually detect and decode a communications signal? Well, folks, you might want to sit down for this one. In some cases, you don’t need the full beam of light anymore and you can interpret the signal one photon at a time.

To best describe this concept of single photon detection, think of each photon in a laser beam as a droplet of water and the laser beam is a river. At the mouth of the river, gallons and gallons of water (photons) are pouring in from a dam (the source of the laser light). Standing in the outlet of the dam would be dumb (just like looking into a laser) and you would need to take safety precautions not to drown (go blind). As the river flows downstream, it widens but no additional water enters the river save for some light rain and maybe Old Man Bill pouring out his beer. Now at the end of the river there’s a well (telescope) for the water about as wide as the outlet of the dam. By the time the water reaches the well, the riverbed is immensely wide, so only a trickle of water finds its way to the well. Imagine you were sending signals about the state of the Cleveland Browns after another disastrous season to your best pal down the river by starting and stopping the flow of water at the dam. Your pal would just barely make out the signals you were trying to send as water droplets falling down to the bottom of the well. Due to the light rain and beer (atmosphere and background light), patterns in the trickle of water are even harder to discern.

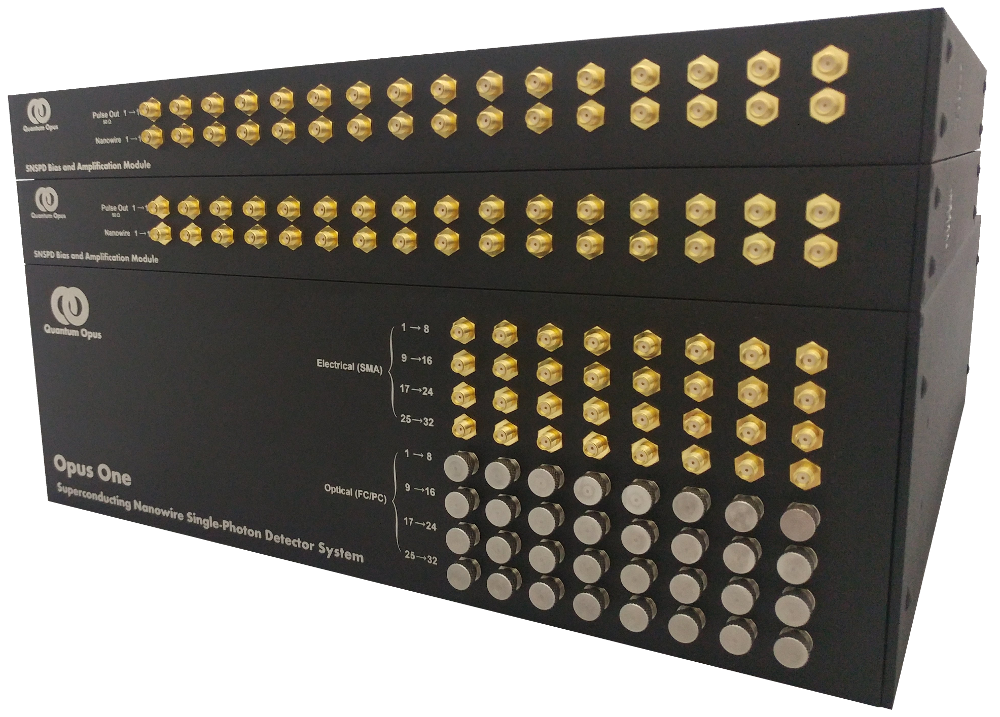

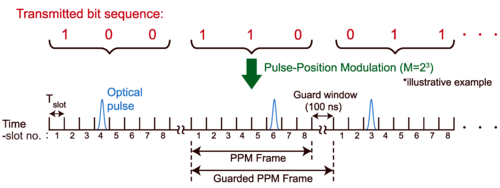

That’s deep space optical comm in a nutshell. A high-powered beam of light made up of photons is turned on and off many millions of times per second to encode a message. Information is encoded in precisely timed light pulses (often using pulse-position modulation rather than simple on/off keying). That beam of light is barely visible, stretched or compressed, and noisy from the atmosphere by the time it reaches a telescope on Earth (the trickle of water), but with modern advancements in superconducting technology, we have detectors sensitive enough to detect an individual photon (droplet of water) in a beam of light.

One inaccuracy about my analogy: the photons travel at the speed of light consistently whereas the stream of water would slow down.

To receive this low photon pulsed optical comm, you’ve got to have a bunch of stuff. The not-so-complete list includes a fancy shmancy telescope, gnarly optics to get light to the detectors, superconducting nanowire detectors, the ability to divvy up the beam into groups of photons (time-binning for the nerds), and digitize the pulses into ‘1’s and ‘0’s. And that’s not all! After that, you’ve got to correct for the Doppler effect of the Earth’s rotation and the velocity of the spacecraft (think of the wee-woo-wee-woo of an ambulance as it passes you, except instead of sound its light), synchronize and separate out groups of transmitted data, and use a crazy decoding scheme to turn those groups into something we humans can understand.

If you’re suffering from insomnia, feel free to read my paper for more details in demodulating and decoding a pulse-position modulated signal using field programmable gate arrays. There have been some unpublished updates and optimizations I’ve made since that paper was released, but that’ll have to wait for another day. For those who don’t want to wade through my technical jargon, think of optical comm as advanced Morse code where you have to know exactly when the transmitter flipped the light switch on and off to understand anything. For the fans wondering what exactly I do, I mostly work on the hardware to decode the signal. The photo below shows an example of how a transmitted sequence can be encoded into optical pulses. You have to know binary to really work out what this tells you, sorry y’all.

Well, this sounds great, right? We’ve already developed transmitter and receiver modems and photon detection technology with commercially available parts. You can’t exactly head to your local MicroCenter and build the thing, but you don’t need to develop much of the modem from scratch either. The back-end optics to gather the light into the detectors has also made leaps and bounds but still requires some real expertise to get right. My project at NASA developed our modem with commercial accessibility in mind, and ANU has since implemented a compatible ground receiver based on the same open and commercial components. We are preparing our ground system in Australia to support upcoming deep-space optical communications demonstrations, including those associated with Artemis-II.

So why are we not seeing multiple camera angles of insane 4k footage live from deep space today? Well, two main reasons: 1. there aren’t enough ground stations that support this type of laser communication. That’s why my team has worked so hard to make these modems accessible. The reason there aren’t more ground stations is because deep space missions don’t use optical comm yet and 2. there isn’t a big enough commercial interest. Photon-counting optical comm in practice is cutting edge technology with not as many uses near-Earth. But when more and more missions take off to explore the great unknown, we’ll be ready.

Finally, as promised, Artemis-II. We’ve all been losing sleep over this mission for the past few years. Artemis-II, for those who are not already aware, is the 2nd test flight in NASA’s Artemis mission series to send humans back to the Moon. Artemis-II will be the first manned test flight to fly around the Moon and back since the Apollo missions in the 60s-70s. This will be a historic return to the human exploration of the lunar surface, and I’m beyond jazzed to be part of it. You can read about the mission here, especially with the approach of the 10-day flight with the first launch opportunity on Feb. 6th.

The reason I mention the mission is because Artemis-II is the season finale of the current deep space optical comm television series, so to speak. There have been many missions leading up to Artemis-II to demonstrate the efficacy of deep space optical comm, and on the Orion spacecraft aboard Artemis-II NASA is expected to demonstrate data rates of up to 260 Mbps with live 4k video streaming, many gigabit file, video, and photo data transfers, high-quality voice calls with the astronauts, and much more. Now I don’t know exactly what they plan to stream during the mission, but that optical link can provide an unimpeded glimpse into what it will really look like as the astronauts approach our favorite moon. If you’re interested in learning more, read up on the Orion Artemis-II Optical Communications System.

I’ll leave you with this. What we do at NASA is explore the great unknown and uncover its secrets to not only benefit the human race but to satisfy our innate curiosity. What then is the point of exploring if we do not share what we find.

Stay tuned for the launch! I’ll share more about my specific involvement after a successful flight.

Ad Astra, and thanks for reading,

Peter

Leave a comment